From April to June this year I was assisting the lovely Bhavna Mehta in the studio as she set about on a very ambitious project as the first artist in residence at the Timken Museum in San Diego. This process has been incredibly rewarding, challenging, and fortifying for my own practice. If you are in San Diego, absolutely make your way down to the Timken to see Leela, admission is always free (they are closed on Mondays). While you’re there, if you photograph the piece, use the tag #leelaatthetimken. She will be in residence through September 16th. Read on for my catalog essay and if you’re so inclined, pick up your own copy with beautiful behind the scenes photos, essays by curators and more from Bhavna at the Timken.

It may strike the contemporary viewer as strange to learn that the Timken’s Portrait of a Lady in a Green Dress is one of many works which do not include the name of the person depicted. Because these portraits were often used to show familial history and idealized values rather than individual identity, they give only half of the story; the other half would come alive through the stories told by the sitter’s family and associates. The objects and clothing shown in painted portraits like the Timken’s were chosen to place its sitter in a specific context through their aesthetic value as well as their symbolic meanings. As an assistant on this project, I have had the unique position of seeing Bhavna make similar choices in the studio constructing a distinct identity for her own woman in a green dress, Leela.

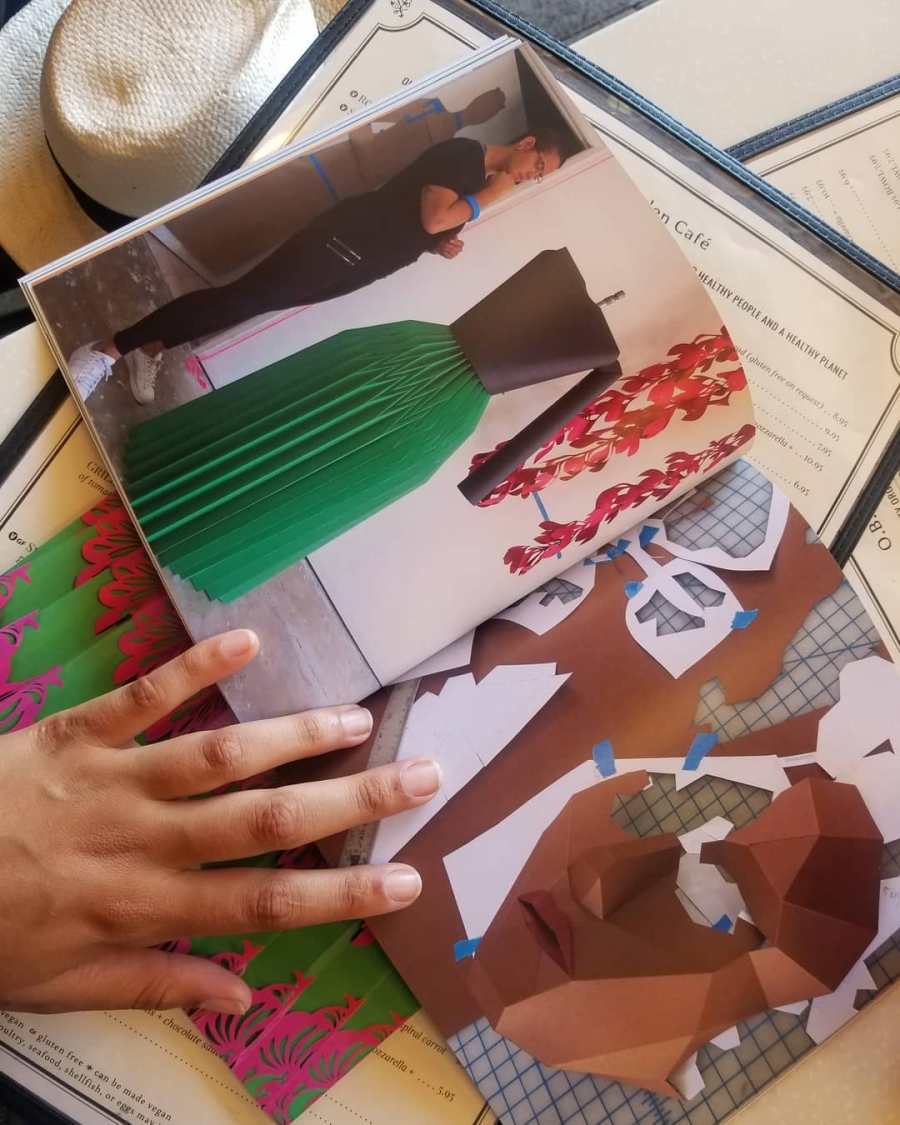

Throughout the time working in the galleries, many guests have asked, “Why is she so big? Was the woman in the portrait really this tall?” Looking at how Veneto has positioned his subject in the frame at a ¾ view we notice her eyes are above the traditional half point of the composition. The use of elevated perspective combined with the size of her gown gives the woman a slightly imposing air. Leela stands at six feet tall, free of a frame altogether. Instead of manipulating materials on a flat panel to give the illusion of depth, Bhavna has manipulated a flat surface expertly into a sculpture that holds its own amongst monumental tapestries in the museum’s atrium. Bringing Leela into the outside world, or bringing the outside world into the gallery with her hanging garden, roots her in the abundance of the natural world, not the dynastic power of a single family. My answer to those who ask is: What is a six-foot tall figure compared to a 60-foot tall tree or the immensity of the ocean? Why shouldn’t a woman be allowed to take up space?

Leela’s skirt radiates outward like a Fibonacci spiral in crisp, repeating folds. Streamers sprout from her puffed shoulders like lilac fireworks widening the span of her ample sleeves even further. Her deep green gown is the color of good luck, balance, and prosperity. It is not the pastel green of early spring shoots but that of a mature old-growth forest. Green has been historically linked to the resurrection or regeneration and is therefore apt for the reintroduction of a set of ideals made for a woman, by a woman with an eye towards expansion. The skirt is punctuated with cut lace that also references nature and her setting in San Diego with floral motifs, abstract fish, and waving water shapes. Placing Leela in a coastal context also alludes to travel and exploration, being on the edge of the unknown or the unseen.

This expansive feeling continues up and out of Leela’s head with a constellation of clues towards her thoughts and ideas. The hair ornament in the painting is believed to be one of four given as gifts by Isabella d’Este who was known to use fashion to demonstrate her own influence by creating trends and aligning herself visually with powerful women of the Roman era1. The wearing of such an accessory would show a connection to Isabella and her court in Milan thereby elevating the status of Venito’s woman. Instead of using Leela’s headspace to align her with the power of another, Bhavna has taken that space to let the story of this woman blossom. Atop her head where a crown might rest is a small brightly colored house, a room of one’s own perhaps. Butterflies and dragonflies circle her head. Arrows, leaves and seed-like spores leap outward from her hair in an uncontrolled burst. The arrows stand out as a break from the natural forms, their presence here feels akin to the use of arrows in American graffiti post-1970’s, expressing dynamism, a wide reach, and a kind of omnipresence. Leela’s thoughts are here, and there, and there, and there, reaching across borders and through time backward to her companion in the Italian gallery and forward through the viewer into the future.

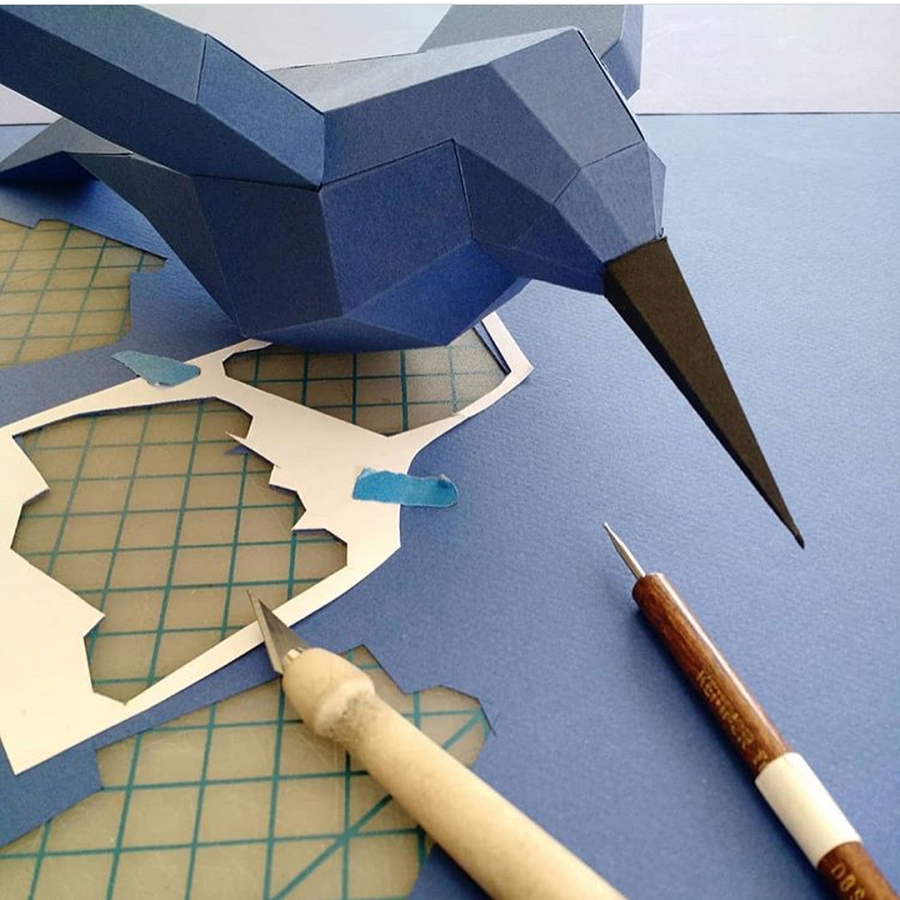

Watching Leela grow from a sketch to a doll-sized maquette, and finally become her distinct self, the way I think about her has evolved as the conversation between her and Veneto’s woman becomes more complex. The relationship between these two women is not one of binary opposites, it is an extended conversation about the shifting roles of women and what it means when we are allowed to tell and celebrate our own stories in our own language. The presence of these remarkable women in the gallery, Bhavna throughout her residency and Leela for her summer tenure, provides viewers with a rich counterpoint to the existing collection and invites guests to rethink the art historical cannon with a global perspective.

1 Tatiana Sizonenko, “Solving the Mystery of the Sitter in Bartolomeo Veneto’s Portrait of a Lady in a Green Dress”, California Italian Studies, 2016